YaaaY We! We Did It! Yesssssssss, We Did It!

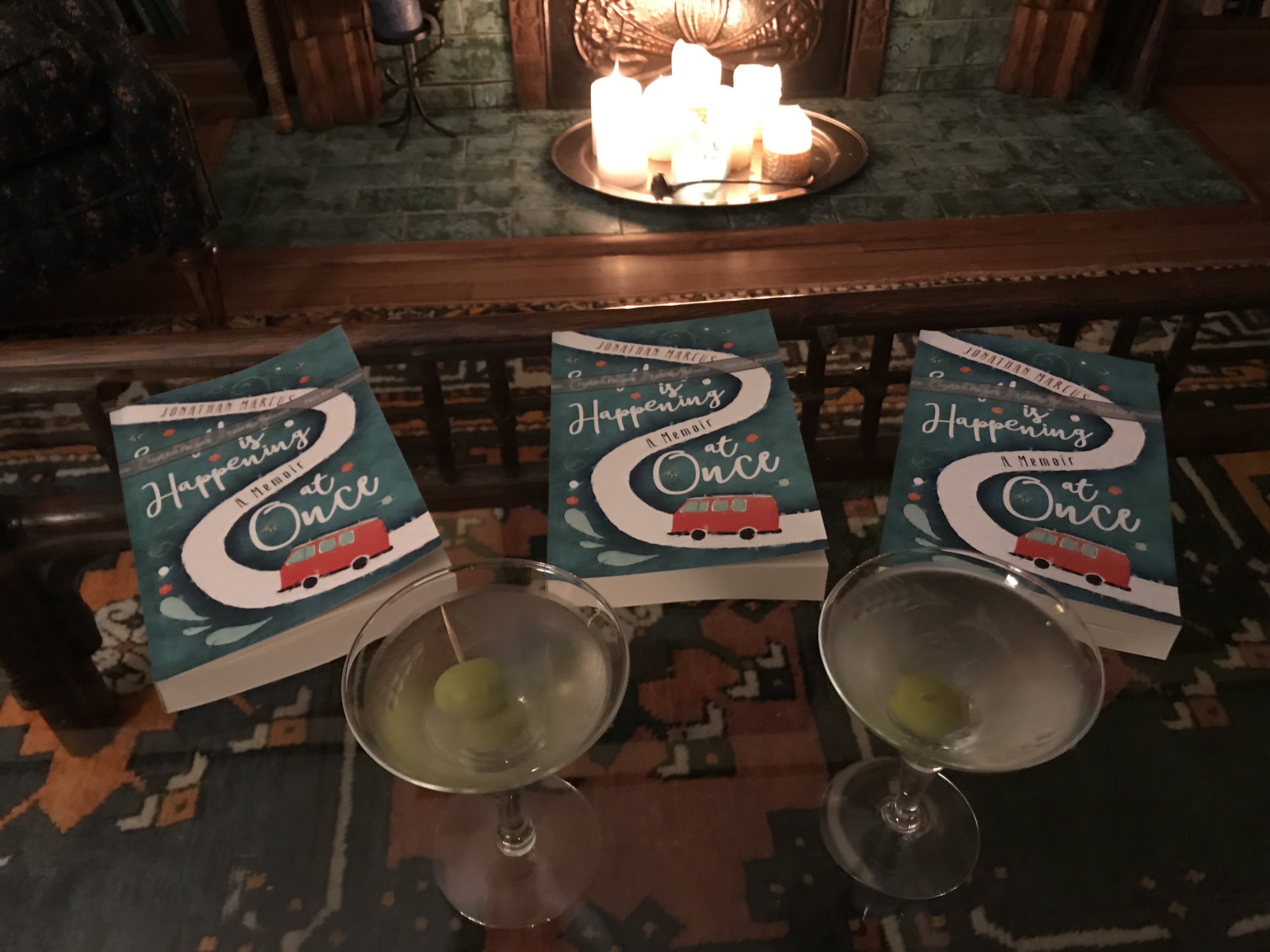

The memoir published by Marcus + Myer, Everything Is Happening at Once, is now available for pre-order on Amazon!

We have given birth. First it was nothing. Then it was a zygote, barely a fat paragraph, a few bumpy spilled words on page one. Now this three hundred and twenty-one page dynamo will meet its audience.

How did this happen? How did nothing become something?

Well, every story contains the story of how it unspooled. Some stories-of-the-story can be so straightforward that they’re hardly stories at all: “Writer produces 2,000 words a day until the novel is done.” Well, that’s great if that’s how you roll.

And then we have the zigzag-what-is-this-and-if-it-is-something-how-will-it-ever-emerge path to completion. Or not.

Everything Is Happening at Once is a product of the latter process.

It emerged as a creature from the ooze without form, intention, or body parts. It burbled shapeless out of the great—meaning horrible—recession that began in 2008.

I had been building houses. Suddenly one day buyers disappeared. One day. Completely. I managed to come out relatively unscathed but relatively unemployed. So I did what all other former homebuilders in Atlanta never do: I signed up for a writing class at Callanwolde, the grand old Candler Mansion repurposed as the Arts Center.

Not that I needed a writing teacher per se. Writing was always a natural engagement with the world, like breathing and eating and walking in the woods. And just like walking in the woods, writing clicked along without expectation. Writing was its own reward: a way to refine the world, a way to milk this life for maximum flavor. Hew life to the page so you might better learn what it is.

As a reader of books, I was able to comprehend that getting published was something writers did, and publication did seem a possible consequence of all this writing, but not especially important and certainly not the object of such a natural activity. It would be like getting paid to walk in the woods.

I signed up for the class not to “learn how to write” or “take a project to market” but simply for the weekly deadline. Something to make me fill pages with words. The written pages would be the reward.

So I was delighted beyond all expectation to find myself in the midst of highly accomplished authors, mostly working on novels. Their sharp observations, critiques, suggestions, questions, and exuberance for fly-off-the-page language crackled like a campfire at my keyboard.

One of my first submissions was a ten page piece called “The Other Way,” about following the Golden Isles Highway diagonally across south Georgia en route to the Florida beaches from Atlanta—instead of the common interstate highway routes. The class loved the writing. The main suggestion was to dig deeper into the experience. These astute readers and aficionados of the written word sensed more. Dig deeper, they said. You’ve written a fine travelogue. Well crafted piece. But you haven’t put enough “you” in the story. So it’s not yet a story.

Hmm, wow. They certainly zeroed in on the crux of the void.

And speaking of “you in the story,” I had written it in the second person—you. “You’re turning left onto The Golden Isles Highway. I-75 disappears in your rear view mirror. About a mile later, you’re outside Perry. You’re alone on a flawless band of macadam.”

I had a thing about not using the word “I.”

One vignette after another. I kept trying. But every time “I” appeared, the sentence would freeze up, and it wouldn’t flow until “you” or “he” or “it” came to the rescue and took the place of “I”. Like an acquired reflex I couldn’t shake, all because of the group I had been in—all the way in—for twenty years. A group we didn’t talk about. It was one of the rules. Don’t talk about it, and don’t talk about yourself, and as much as possible, don’t use the word “I.”

But finally, after too many I-can’t-say-I classes later, and urging from my cohorts, the hell with it, I broke loose and the reflex shattered. I spilled onto the pages the truth of an indelible episode that no one had ever spoken about, that day on the lake. It came alive again through my fingers. On the keyboard. In the first person.

In the middle of the twenty years in the group, on that long-ago balmy spring day, we were zipping around the lake in Sam’s speedboat. It was supposed to be fun. And it was at first, it was a blast, Sam throwing the boat into tight figure 8s, starboard and port taking turns airborne, then burrowing down and slicing the black lake, everyone thrilling along. Until the Guy-in-Charge dragged his forefinger across his throat. Sam cuts the motor. Boat draws up in the middle of the giant lake. And those Guy-in-Charge rock hard green eyes bore into the new guy who had just attended a few meetings and the Guy-in-Charge said, “Jump in the lake.” The new guy, pudgy and impossibly white, got a lot whiter and said, “I can’t swim.”

Everyone in the class loves the story. Gripping, they say, on the edge of my seat, what a departure, we want more, where did you get this?

But the teacher of the writing class, a published author herself, shouts everyone down, demands silence, and launches into a breathless diatribe, bashing this hollow failure that is not a story at all but just an insult to the reader, and who would want to make up such a thing, let alone why would anyone want to read such miserable drivel.

As she ranted, it registers, yes, I have a story here. She hates it + they love it + I want to chisel the truth out of the wild twenty year full spectrum fandango and plant it on the page = this is the story, and I’m gonna tell it.

That’s how the zygote formed. The memoir. From nothing to these few pages in the middle of it all. That’s how it started, it started in the middle. The story that wasn’t supposed to be told. So obvious now: I have to tell it. It’s the only way I know to figure out what in the hell all that was all about. Clarity. A project. A mission. Focus.

Now that I know what I’m doing, the path is clear. And straightforward. It’s the memoir of what actually happened in that closed whirl. I can just tell the story. I imagined being one of those two thousand word a day guys who just cranks it out in a few months.

But no. The zigging and zagging has just begun.

I quit the class because the teacher, talented wordsmith or not, was a judgmental maniac.

And before even wondering how to get from the middle of the story to the beginning, I graft myself to a chair on the beach in north Florida, where my grandparents had lived out their days. I call it primary research. For the memoir. This is nonfiction. We need facts. But I wasn’t shuffling through archives in the Volusia County Courthouse or perusing faded photographs in an ancient attic. I sat with a pen and journal while an arthroscopic bloodhound traipsed neural pathways, sniffing out memories that had been sealed since inception. It was archaeological, and it was physical, I could feel it in there, the hunt, following the scent, and then zeroing in. Surgically one-by-one, with the light of attention, unlocking sealed memory kernels and writing them down. Gathering the facts.

Serendipitously, as if orchestrated by life itself, another primary research document appears out of nowhere: Grandpa’s autobiography. Hand-written, in dense, loopy script. Hard to read. Of all the relatives in our loquacious family, he was the one we as kids knew the least—and he is the only one to have shared his life story like this. He left his family in Poland with no money, alone, at age sixteen, landed in New York, and after sacrificing his youth, became a wealthy fur broker. And I am the only one who’s read it.

Three of us refugees from the class began our own writing group. New pages flowed to the regular deadlines, and the memoir that formed on the empty pages was a structurally risky braided together marriage of stories united by their fundamental urges, including my twenty years in the old group, and Grandpa’s struggle to make a new life in the New World. My partners in the writing group loved it.

Three years later. I have a finished manuscript. Now what? Would the publishers please form a line and bid for the rights . . .

I moved to Richmond, Virginia.

Zigzag.

I joined the very active James River Writers group, and attended a class they sponsored, “Social Media for Writers.” Sat next to a published author. We became friendly. At the end of the day, I asked her the dreaded question. “Would you like to read my manuscript?”

She loved it completely, asked me where did I learn to write like that, and she told her agent in New York, “You have to read this.”

The agent said, “This is beautiful writing, but nobody will ever buy this book the way it’s written. Nobody wants to read about your multiple stories braided together, no matter how cleverly you’ve pulled it off. But if you really want to tell the whole story of what happened in that group, everyone wants to know. Everyone wants to know what’s behind the locked door at the end of the long dark corridor.” I rewrote it completely. It’s a different manuscript, and it delves all the way into the nuts and bolts and glories and travesties of what went on behind the locked door.

And in the process, life imitates art. Cyndy Myer, my girlfriend from 1980, appears on page 207 as I’m writing the new manuscript. Then, practically the next week, she contacts me for the first time in thirty-five years, and we reconnect in real life.

And now, in October, 2018, Cyndy and I are publishing the book together, and as of last week, it’s available on Amazon. Zigzag of my dreams!

The zigzag zygote of gestation and labor. The memoir of twenty years hewn to the pages by the twenty years that followed.

One More Time, Everyone All Together Now:

YaaaY We!

We Did It!

Yesssssssss,

We Did It!

The memoir published by Marcus + Myer

Everything Is Happening at Once

is now available on Amazon!

We have given birth.

First it was nothing.

Then it was a zygote,

barely a fat paragraph,

a few bumpy spilled words on page one.

Now this three hundred and nine page dynamo

will meet its audience.